Tomorrow would have been my father’s 87th birthday. I would have called him on Facebook Messenger, connecting to the Facebook Portal I bought my parents many years ago because its single-purpose design was easier for them to navigate than a desktop or laptop computer with a webcam and video conferencing apps. Along with wishing him well for his birthday, we would have talked about the upcoming Thanksgiving holiday, and I would express my gratitude to him and my mother. We’d talk about the prospects of his favorite pro football team, the Dallas Cowboys, as they hosted a Thanksgiving Day National Football League game for the 57th time, this one against the moribund New York Giants. I would have asked him if they had anything special planned for his birthday, knowing that in recent years, they didn’t go out much, and if they did anything, it would be at home if the family remembered to do something for him. Finally, I would have repeated my birthday wishes and told him I loved him.

Sadly, I won’t have that opportunity. Dad didn’t make it to his 87th birthday.

I did a video chat with him on October 3rd, my mother’s birthday, and he seemed fine. He struggled with several ailments - neuropathy in his right arm, blindness in one eye due to glaucoma, and diabetic leg wounds - but he didn’t have abdominal pain until a few days after we chatted. He saw a doctor and was sent home, but the pain worsened. When it became unbearable, he was transported to the hospital, and this time, he was admitted for emergency surgery to remove a potentially lethal bowel obstruction. I spoke to him by phone on October 8th before the surgery, and I am glad I had a chance to tell him I loved him and would be praying for him. What was supposed to be a laparoscopy turned into major surgery requiring an incision from his sternum to the waist, and the internal damage they discovered was extensive. They removed a portion of his colon, and while he emerged from the surgery, he was in a great deal of pain. I was concerned about the physical trauma surgery of that magnitude inflicted on him, and on Sunday, October 13th, his weakened body began failing him. He was transferred to the intensive care unit, and he passed away early on the morning of October 14th.

Dad’s death was yet another reminder this year of the passage of time and our mortality on this side of eternity. My father-in-law, Henri Aeschbach, died on Valentine’s Day earlier this year, and my wife now navigates a world without her father and her mother, Charlotte, who died over two years ago. I loved my parents-in-law, and in my tribute to them, I mourned their loss and celebrated the place on the other side of the world where I first met them, and they welcomed me into the family; it was “the place where my love story and the greatest family a man could ever have began.” Our wedding anniversary was on the same date as theirs - July 14th, which also happens to be Bastille Day - but they were not with us this year to celebrate our 40th and what would have been their 68th.

In July, we euthanized our older family dog, Daisy, who was suffering from degenerative myelopathy and could no longer use her back legs. She was increasingly incontinent, which meant the disease was advancing. Letting Daisy go was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done; although she was nearly 12, we had her for only five of those years, and our time with her seemed far too short. Also, while her veterinarian assured us that her incurable condition warranted us sparing her from further suffering and the eventual onset of complete paralysis, it felt wrong to make that decision for her. The process was merciful, and the entire family, even our younger dog Marlo, was there with her so she didn’t die alone. Still, I was wrecked, especially for my daughter Briana, who always loved corgis and adopted Daisy from the Lynchburg Humane Society as a birthday present in 2019. The day before we put her to sleep, Briana gave her the best day ever - a car ride, a pup cup, chicken McNuggets for lunch, sirloin steak for dinner, and a good night’s sleep in the bed with her. I hope she felt special and loved on her last day. I don’t know if our pets go to heaven, but I desperately hope she is running again through green pastures and free from the disease that crippled her.

When I saw my father in his casket the day before the funeral, I was unexplainably comforted by how peaceful he looked. I mentioned that he was ailing; he once told my younger brother, who inquired about his health, that “everything hurts.” At the same time, he was taking care of my mother, who suffers from dementia, and looking after a household where my uncle, a nephew, and a brother also lived because they had no places of their own. As a patriarch, he bore many burdens for the family and community while struggling with his health and well-being, and as I gazed upon his still form, the Lord assured me that he was finally at rest and forever free. I was liberated to be present for my family, especially my mother, during the funeral service the next day, and I was able to pay tribute to Dad with a strong voice and a calm heart. The outpouring of love from the community was incredible; the people turned out for his funeral, and we were inundated with cards, letters, texts, social media posts, floral arrangements, and meals. Truly, my father was loved and respected.

The following Monday, we accompanied my father from the funeral home to his final earthly resting place at the Central Louisiana Veterans Cemetery. The cemetery was an hour and a half away from Lake Charles, so my youngest brother, Jeff, an assistant chief deputy sheriff with the Calcasieu Parish Sheriff’s Office, arranged for a sheriff’s escort for our procession. As we reached the Calcasieu Parish border, sheriff’s deputies from the next parish picked up the escort detail, which occurred repeatedly as we crossed jurisdictions to ensure we had an official escort to the cemetery from beginning to end. I was so moved that they would honor Dad this way.

We arrived at the cemetery and participated in a brief ceremony with an Air Force honor guard, a three-rifle volley, taps, and the folding and presenting of the flag to my mother. It was a beautiful, sunny day, and before we departed the cemetery, leaving him to be interred in the Louisiana soil that had been his home, I touched the casket and said farewell.

I loved my father, and while he said my achievements made him proud, I am who I am because of him. I want to share his story with you if you'll indulge me for a little while.

Lafayette Miller, Jr. was born in Marshallville, Georgia, on November 24, 1937, to Lafayette Miller, Sr. and Lula Mae Fuller, who were 17 years old. Shortly after his birth, his father moved to Detroit, Michigan, leaving him with his mother, who struggled to make ends meet. He grew up in Marshallville, worked on his uncle Harris’ farm, and “lived with him off and on,” according to family lore. In a previous article about my family history, I wrote about how the Millers emerged from slavery to build new lives for themselves in central Georgia. My third-great-grandparents, Fred “Fed” Miller and Lucy Ann Matthews, gave each of their sons land and livestock to get started, and they made the most of what they were given. I previously wrote about the success of one of them:

Speaking of Fort Valley, Georgia, my 2nd great-granduncle, James Isaac “Ike” Miller, was, as his obituary described, “a self-made man.” Born into slavery, he was determined to make his own way in life, and he purchased his first 50 acres of land in 1885. By the time of his death, he owned about 1,300 acres in Crawford and Peach counties, and he had over $82,000 in the bank along with bonds and other assets. He was one of the founders, a benefactor, and a Board of Trustees member of what is now Fort Valley State Univesity, one of the few colleges in the country to be founded by former slaves. The Isaac Miller Science Building was dedicated on campus on November 24, 1963, the day after President Kennedy was assassinated. Miller Hall, which featured science laboratories, lecture halls, and an assembly auditorium, was renovated in 2012 and converted into academic classrooms and office space. You’ll find Isaac Miller in a collage of some of FVSU’s founders if you click here.

Dad’s great-grandfather, Cornelius, apparently owned over a thousand acres of land in and around Marshallville. Family accounts indicate that his agricultural enterprise included “cotton, peaches, pecan nuts, cattle, milk, and trees;” he also owned and operated a lumber mill and seed mill. A portion of his wealth was passed down to his grandson, Dad’s uncle Harris, who cared for my father “off and on.” One family member said that while Dad’s mother was poor, he knew his Miller kinfolk were always there with a job, a meal, and a place to live.

Eventually, Dad relocated to Detroit to be with his father, who married and had four children, Harold, Sandra, Jamie, and Perez, with his wife, Edna Clayborn.

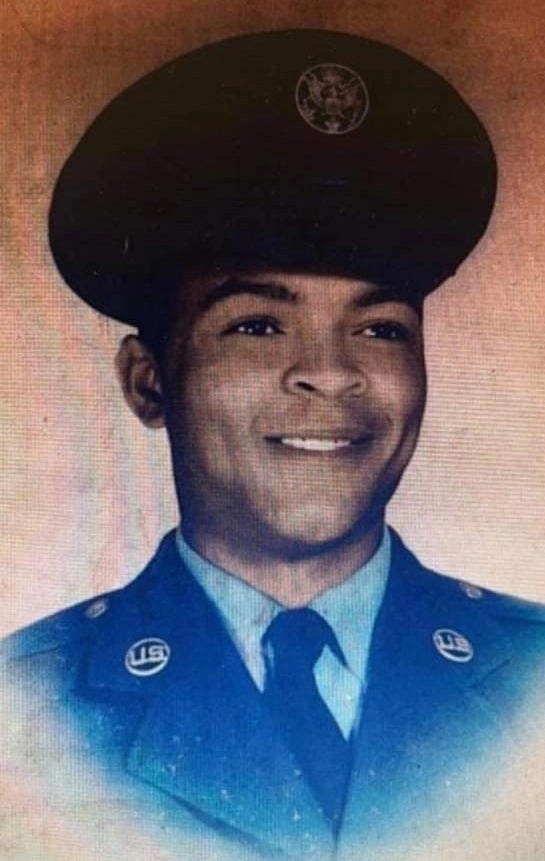

From Detroit, he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force in 1957. After basic training, he was stationed at Chennault Air Force Base near Lake Charles, Louisiana. There, he met my mother, Mary Jean Lubin. They married on May 1, 1959, and began their life journey together.

We traveled the world, living in Alaska, Indiana, Japan, Idaho, New Mexico, Spain, and Texas, with occasional stops in Lake Charles for a few months if Dad was at his next duty station preparing to receive the family, or up to a year if he was on a temporary duty assignment that didn’t allow us to accompany him. He was a munitions maintenance specialist and supervisor, “ensuring that weapons and missiles are fully stocked, functional, and ready for deployment.” While he was fortunate never to have been stationed in Vietnam during the war, at least one of his temporary duty assignments was ensuring that aircraft deployed from Thailand had the weapons they needed to carry out their missions in the war zone. He spent much of his Air Force career with the Strategic Air Command (SAC), so his duties included the maintenance of nuclear weapons delivered by aircraft. Ironically, my first duty station as an air intelligence officer was SAC headquarters at Offutt Air Force Base, Nebraska.

My father served in the U.S. Air Force for 22 1/2 years, retiring in 1978 as a master sergeant. The family moved back to Lake Charles while I was in college and preparing for my own career in the military.

After leaving the military, he worked for Consolidated Aluminum Corporation and Gulf States Utilities (now Entergy Texas) until his civilian retirement. Still, he continued to work at a beauty and supply store near their house on Pineview Street and as a school crossing guard. As long as Dad’s health allowed, he was doing something - working, tending to his garden, or going to the local Wal-Mart to shop and meet people. It must have been hard for him to give those things up as his health gradually robbed him of his ability to drive or spend much time on his feet.

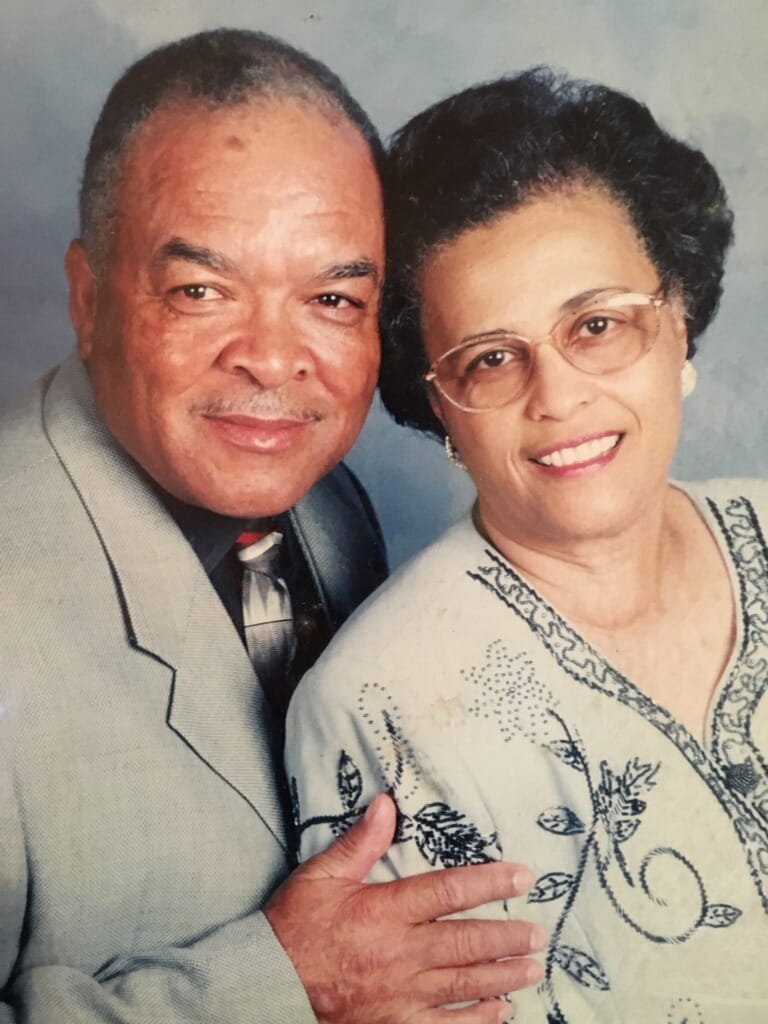

At the time of his passing, he and my mother had been married for more than 65 years and had four children: me, my brothers Kevin and Jeffrey, and my sister Jeanise.

My father learned late in life that he had a son, Al Steven Lane, from a relationship that preceded his enlistment in the military. I remember him calling me while my family and I were stationed in Germany to tell me I wasn’t his oldest child. It must have been a shock to learn 30 years later about a son he’d never known. I’ve never met Al in person, although we are connected through social media. However, I know he and Dad met and made a positive connection.

Besides what I've shared, I don’t know much about Dad’s upbringing. An episode from a family trip in 1972 makes me believe that some wounds needed to be healed. We were driving from Lake Charles to Charleston, South Carolina, where we were to board a plane to Dad’s next duty station at Torrejon Air Base outside of Madrid, Spain. We had left Birmingham after a sleepover, and Mom had taken over driving duties with instructions to take the interstate highway to Atlanta. Somehow, Mom got turned around, and we were heading toward Macon. Dad had been napping in the passenger seat, and when he awoke and realized Mom's mistake, he was somewhat distressed! Mom then suggested to him that, since we were already headed that way, we should stop in Marshallville and see his mother. What transpired next was a heated argument, and we four kids were trapped in the back seat while our parents raged at each other. Mind you, none of us had ever met our grandmother in Georgia, and I don’t recall meeting our family in Michigan when I was a child. My dad’s brother Harold was our only consistent connection to Dad’s family; he had numerous brothers and sisters, most of whom we didn’t know existed. Dad had essentially claimed my Mom’s family as his own and didn’t seem interested in his. On that drive toward central Georgia, it was pretty clear that he didn’t want to see his mother, but my mother was determined to bring them together, and she won the argument.

I remember us pulling up to a dilapidated house in a rural area outside of Marshallville. Dad got out of the car to go toward the front porch as a matronly old black woman emerged, looking at Dad warily. She didn’t recognize him at first, but he said, “It’s Pap,” a nickname given to him as a child. She instantly dissolved into tears and went to hug him, and the rest of us determined it was safe to get out of the car! That was the first time I met my paternal grandmother, Lula Mae Fuller.

Decades later, at a 2000 family reunion in Vinings, Georgia, I spent a delightful afternoon interviewing her and learning more about her life. She had eleven children with five different fathers, and despite living what appeared to be a hard life in relative poverty, she had a serenity about her that amazed me. She and my Dad reconciled that afternoon in 1972, and she even visited him in Lake Charles and had a chance to see what he had made of his life. Dad returned to Marshallville in 2005 for her funeral and was reunited with his brothers and sisters from the Fuller branch of the family tree.

Dad was well-liked and respected by everyone he encountered because he was kind. He taught me, “You catch more flies with honey than vinegar.” I liken that old saying to my life verse in Romans: “If possible, as far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all” (Romans 12:18). It amazed me how many people he knew from his days on active duty that would travel to Lake Charles to honor him for his kindness in their lives. I said at his funeral that “he was everybody’s grandfather,” and the attendance at his funeral was a testament to how beloved he was.

He’s going to celebrate his first birthday in heaven tomorrow. I miss him, and I’m saddened that I won’t be able to see him or talk to him. I was so blessed to have him as my dad.

Ron, Thank you for sharing your love for your dad. I hope your writings brought you solace in the wonderful memories shared. I am left with a personal question that you can ignore if you prefer - Who will now take care of your mom?